How is climate change affecting the Antarctic Peninsula? And how will the Antarctic Peninsula change under future climate?

These questions are tackled in Davies et al. 2026, which analyses climate model outputs for three scenarios: SSPs 1-2.6, SSP3-7.0 and SSP 5-8.5. These reflect a sustainable future, a medium-high emissions future and a high emissions future respectively. We argue that choices made today, in the decade 2020-2030, are critical for the future of the Antarctic Peninsula. Once thresholds are crossed, we cannot return – even if we eventually do cut carbon.

We build on a previous, more optimistic report on the future of the Antarctic Peninsula under 1.5°C of warming by 2100. Unfortunately, this now looks out of reach.

Highlights

The Antarctic Peninsula is warming at twice the rate of the global average (0.27°C per decade).

Substantial and irreversible damage occurs if global warming exceeds 2°C.

Changes in the Antarctic Peninsula have global consequences. Sea ice loss, ice shelf collapse and glacier mass loss will result in self-sustaining processes that will amplify polar warming and influence global climate, sea level and ocean circulation.

Changes on the Antarctic Peninsula will influence species migration and loss, with impacts on krill, fishing, and food chains for large marine predators like whales, seals and penguins. Extreme events have already devastated penguin colonies, for example through sea ice loss or flooding of breeding colonies.

Following through and achieving the country pledges and net zero targets put forward at COP30 would avoid the most significant impacts by keeping global warming to less than 2°C.

The scenarios

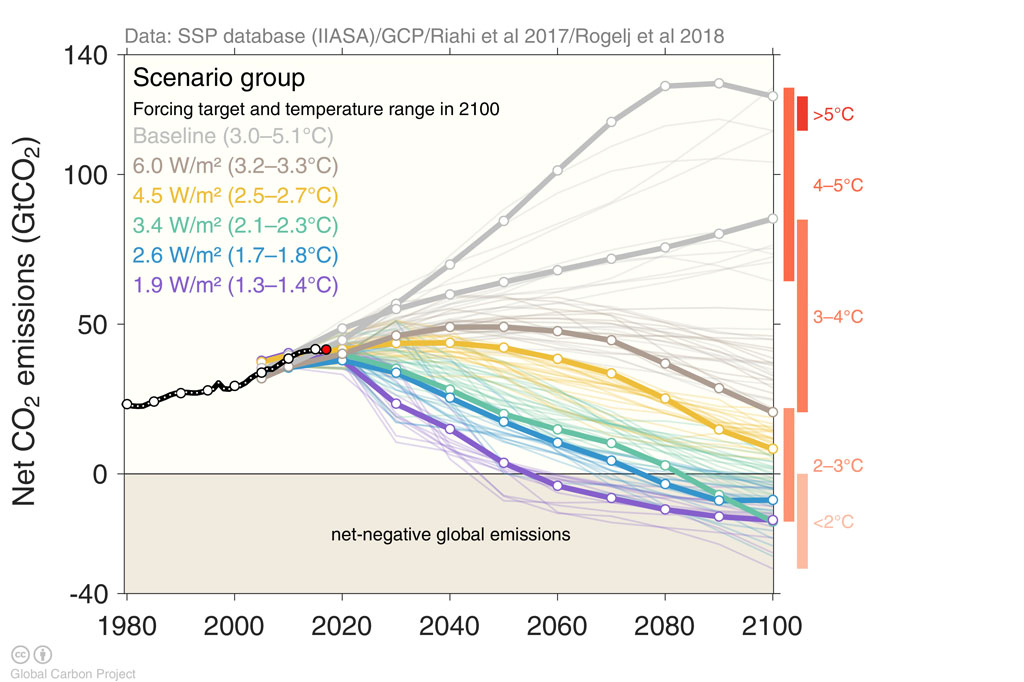

Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) are used by climate models to predict the future. They are imagined futures with carbon projections and pathways. The Scenarios have a framework of their SSP (1-5) combined with the expected level of radiative forcing in watts per metre squared by the year 2100 (1.9 to 8.5 W/m2).

SSP1 is a ‘sustainable’ future, the ‘green road’. CO2 emissions reach net zero around 2050 for SSP1-1.9 and has an estimated warming by 2081-2100 of 1.4°C (very likely range 1.0-1.8°C).

SSP1-2.6 has CO2 emissions reaching net zero at 2075 and has an estimated warming of 1.8°C (very likely range 1.3-2.4°C).

SSP2 is a ‘middle of the road’ scenario, where CO2 emissions slowly decline to 2100. Social, economic and technological patterns remain similar to today, and global nations make slow progress towards achieving sustainable development goals. SSP2-4.5 has intermediate greenhouse gas emissions, with estimated warming at 2100 of 2.7 °C (2.1-3.5°C ).

SSP3 is ‘regional rivalry’, with resurgent nationalism, concerns about competitiveness and security, and regional conflicts leading to countries focusing more on domestic or regional issues. CO2 emissions double by 2100. SSP3-7.0 has an estimated warming of 3.6°C by 2100 (very likely range 2.8 – 4.6°C).

SSP5 is ‘Fossil fuelled development’ with exploitation of fossil fuel resources. CO2 emissions triple by 2075. For SSP5-8.5, global estimated warming by 2100 is 4.4 °C (very likely range 3.3-5.7°C).

Current global warming

Current global warming reached 1.34–1.41°C relative to 1850–1900 CE (WMO State of the Climate 2024), with an average trend of +0.27°C per decade since the late 1970s (Forster et al 2025).

Policies as of COP30 in 2025 are only enough to keep global warming below 2.8°C by 2100 (range 2.1-3.9°C), and the change of remaining below 0°C is 0% (UNEP). Achieving all country pledges and long-term net zero targets would lower this to 1.9°C (range 1.8-2.3°C).

The changing Antarctic Peninsula

Atmospheric warming

The Peninsula has been warming at 0.3 to 0.5°C per decade since the 1950s, roughly twice the rate of global warming.

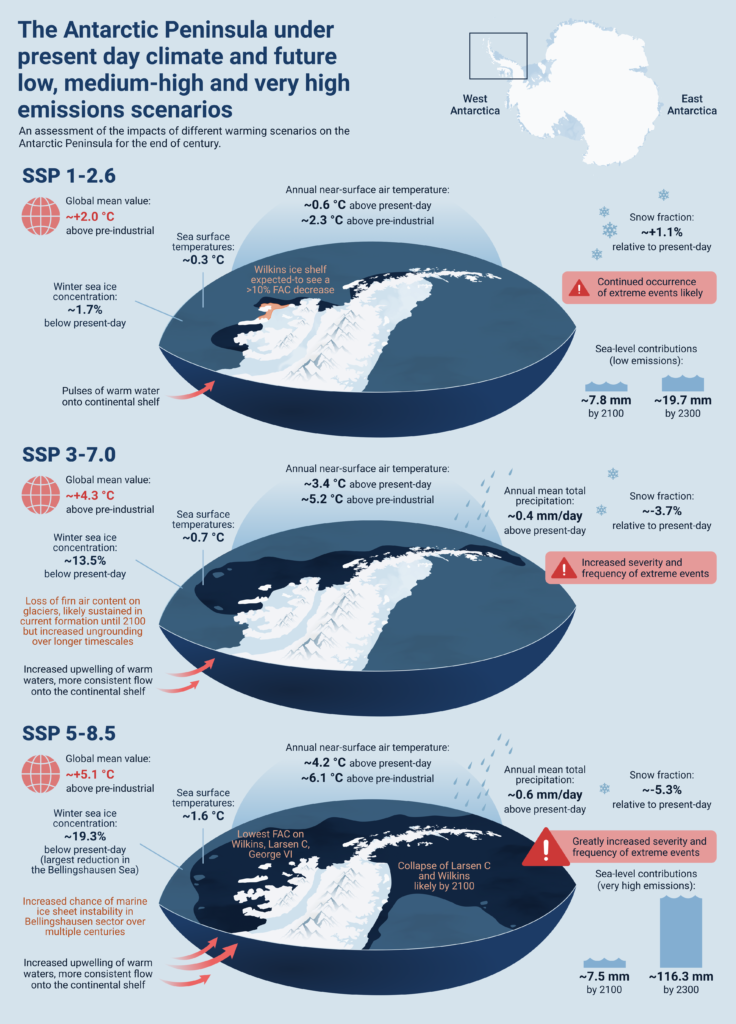

Following SSP1-2.6 would see warming on the Peninsula of 2.4°C, +0.6°C warmer than the present day.

SSP3-7.0 would see warming of 5.0°C, +3.4°C warmer than the present day. The fraction of precipitation falling as rain would increase slightly, particularly in the summer. The number of days above 0°C would increase from 19.7 days today to 38.7 days.

SSP5-8.5 would see warming of 5.8°C, +4.2°C warmer than the present day. This is far higher than the projected global mean. The fraction of precipitation falling as snow would decrease by 5.3%, and the melt season would increase in length. The number of days above 0°C would increase to 48.1 days.

The higher emissions scenarios would increase surface melt on Peninsula glaciers and ice shelves, and encourage sea ice to melt earlier.

Extreme events

Extreme events are already happening on the Peninsula. Exceptionally high temperatures in February 2020 and 2022 resulted in very high surface melt conditions, reduced sea ice, and the failure of some emperor breeding colonies.

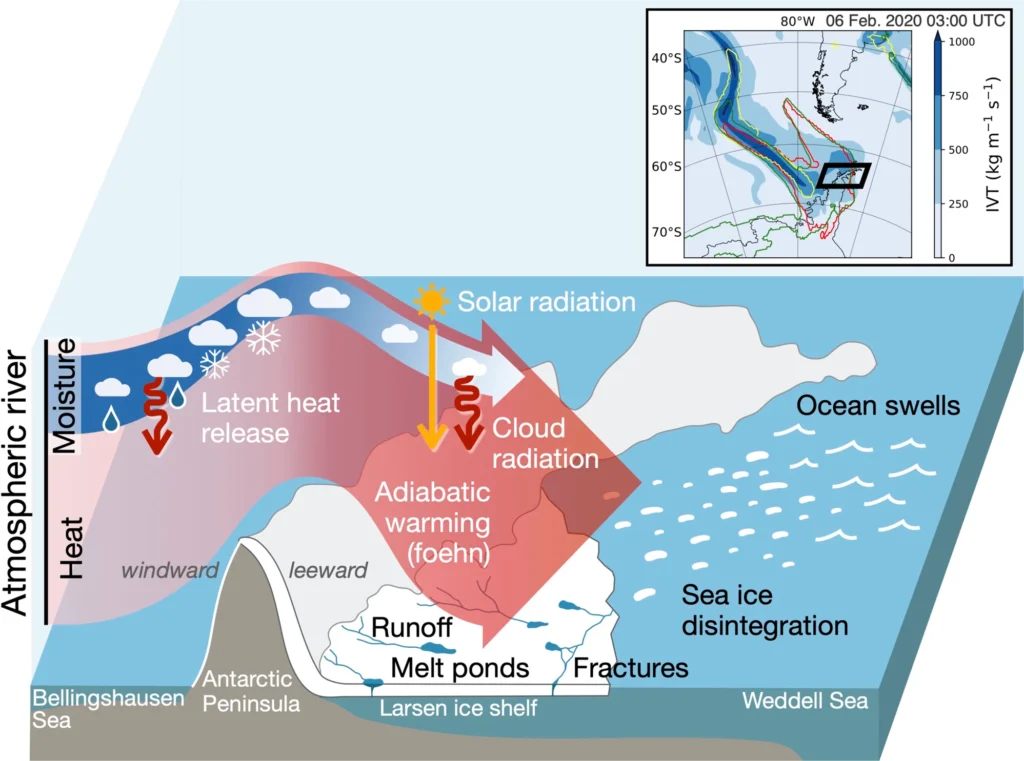

Atmospheric rivers, which are long corridors of moist air, delivered extreme precipitation and warmth to the Peninsula. In July 2023, an atmospheric river brought temperatures of +2.7°C and rainfall to the peninsula in the depths of winter. On the lee side of the mountains, they can result in warm, dry winds (foehn winds), that drive high surface melt conditions (Wille et al., 2022).

Both heat waves and atmospheric rivers are predicted to become more frequent and intense on the Peninsula, with much stronger trends under higher emissions scenarios.

Ocean heating

The ocean around the Peninsula is already heating up, and increased winds are bringing increased upwelling of Circumpolar Deep Water to the Peninsula. This melts glaciers at the grounding line, where they start to float off the sea bed, leading to rapid glacier recession.

Southern Ocean sea surface temperature warming by 2100 is ~0.3°C for SSP1–2.6, ~0.7°C for SSP3–7.0, to ~1.6°C for SSP5–8.5. Under lower emissions scenarios, upwelling Circumpolar Deep Water is limited to pulses onto the continental shelf, but becomes more continuous under higher emissions scenarios.

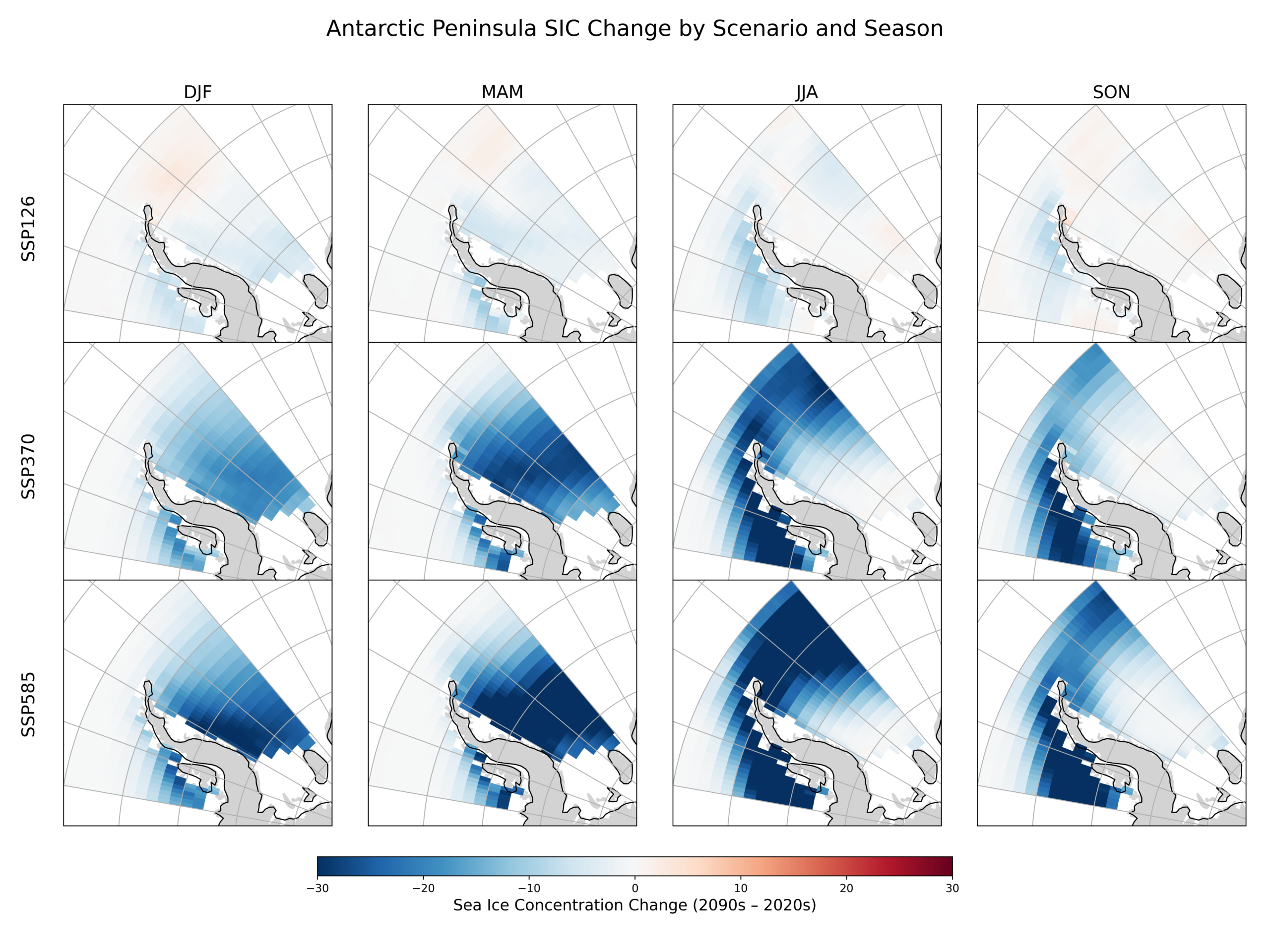

Sea ice (frozen sea water)

Winter sea ice extent in the Bellingshausen Sea has been shrinking since the 1970s, and since 2015 in the Weddell Sea. Sea ice has been declining continent-wide since 2016.

Under SSP1-2.6, sea ice changes around the Peninsula remain modest til 2100. However under SSP3-7.0, summer sea ice reductions of 10% are likely. SSP5-8.5 would result in summer reductions of 12% and winter reductions of 20%.

Summers with low sea ice encourage more glacier calving, enhancing glacier recession. They also change the rate of Antarctic Intermediate Water formation, affecting ocean circulation. This would impact ocean heat and carbon uptake, and impact marine ecosystems. Loss of Antarctic sea ice would reduce albedo, amplifying polar warming.

The loss of sea ice therefore risks becoming a self-perpetuating process, and a tipping point that, once crossed, is irreversible on human timescales.

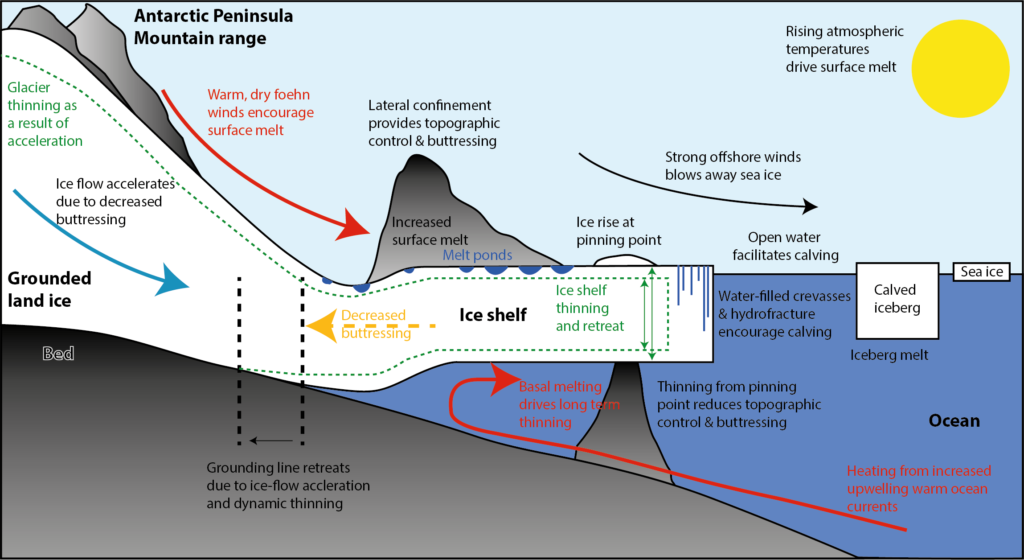

Ice shelves (floating extensions of glaciers)

Ice shelves fringe 75% of Antarctica’s coastline. They support glaciers by buttressing the flow of inland glacier ice. They are vulnerable to heating from both above and below. Increased melting from below, associated with more upwelling of Circumpolar Deep Water, is driving long term thinning and decreasing buttressing.

Regional warming is increasing surface melt and meltwater ponding on the ice shelf surface. This can destablise ice shelves through hydrofracture, leading to ice shelf collapse. Reduced landfast sea ice can further accelerate the calving of icebergs from ice shelves.

These processes have already led to the collapse of ice shelves on the Antarctic Peninsula: Prince Gustav Ice Shelf in 1995, Larsen A in 1995, and Larsen B in 2002. Following such collapses, the grounded glaciers upstream accelerated and thinned, discharging more ice into the ocean.

More frequent heat waves and atmospheric rivers will increase surface melt over the remaining ice shelves, while ocean heating will melt ice shelves from below. Surface melt is projected to increase under warming of 2-4°C for many ice shelves. Under SSP5-8.5, the Larsen C and Wilkins ice shelves could collapse by 2100.

Ice sheet simulations that include ice shelf collapse result in significantly higher sea level rise contributions.

Land ice (glaciers grounded above sea level)

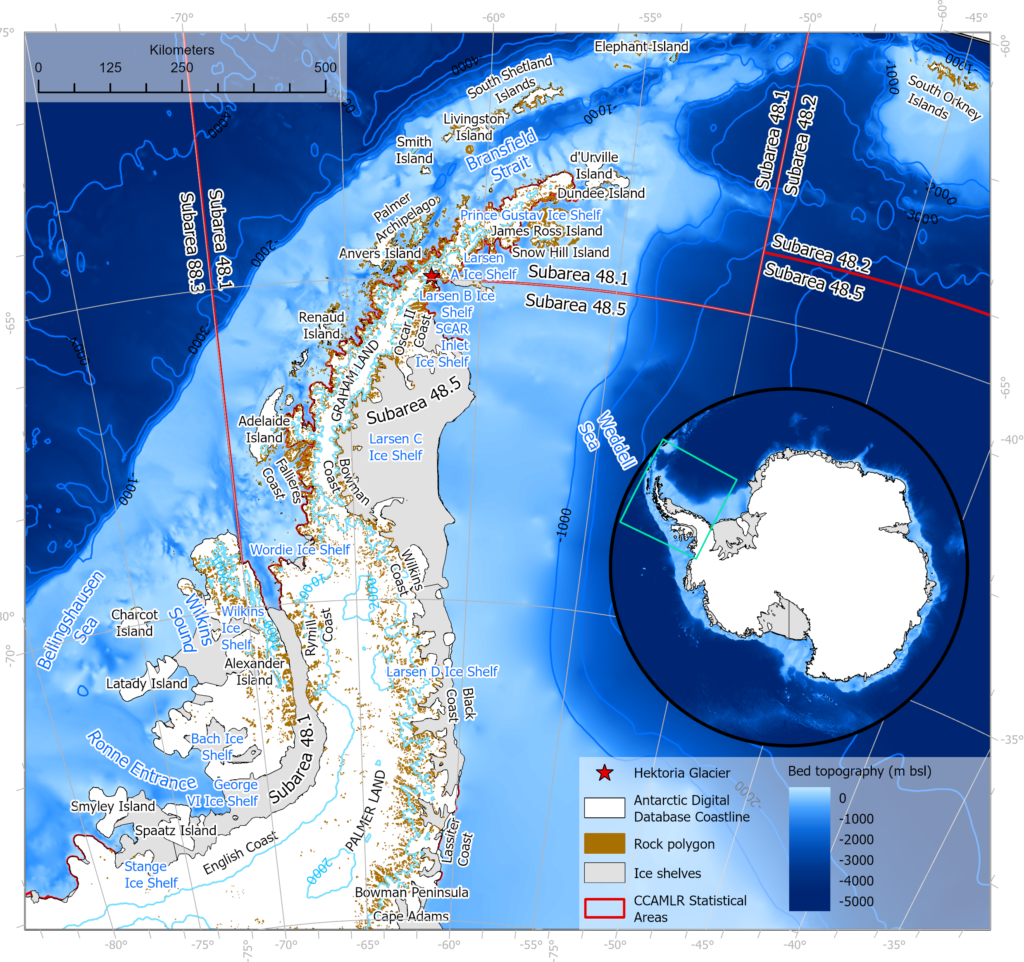

Glaciers are currently receding on the Antarctic Peninsula, losing 13 billion tonnes of ice per year. Record rates of glacier recession have recently been observed at Hektoria Glacier on the northern Antarctic Peninsula, reaching 8.2 km from November to December 2022.

The glaciers are receding due to a combination of atmospheric and oceanic warming, disintegrating landfast sea ice, and glacier acceleration following ice-shelf thinning. This mass loss contributes to sea level rise, and darkens the region. This darkening lowers the albedo, driving regional warming.

Under SSP1-2.6, these trends will continue, but some mass loss may be offset by higher snowfall. Under SSP3-7.0, increased runoff could mean that more meltwater reaches the base of the glacier, leading to seasonal glacier speed-ups.

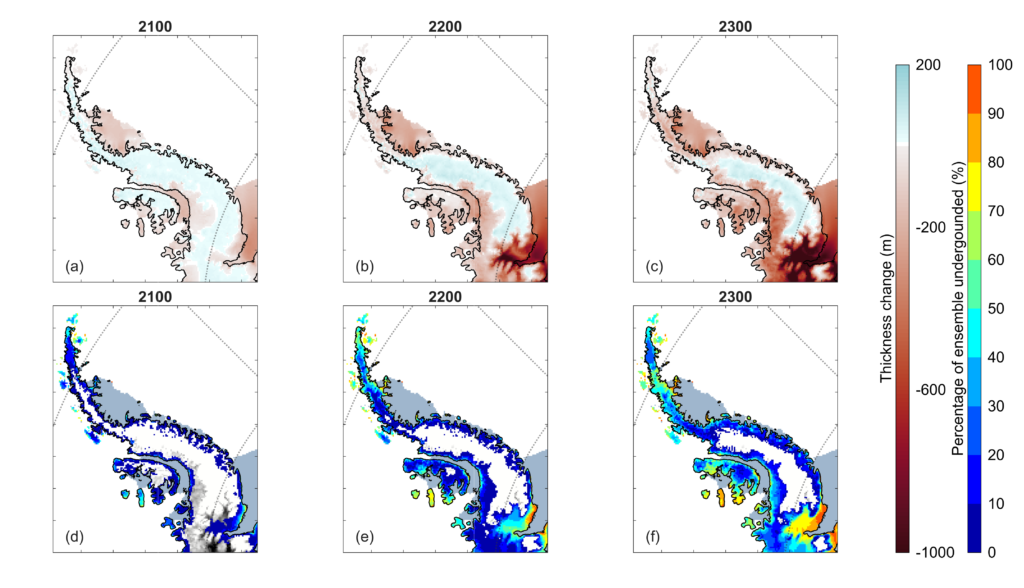

Grounding line retreat is likely under SSP5-8.5, with the Bellingshausen Sea particularly vulnerable. Positive feedback processes such as ice shelf collapse or marine ice sheet instability in this region will make this recession both rapid and irreversible.

Sea level contributions will vary under the different scenarios. Under SSP5-8.5, sea level rise could be 7.54 ± 14.13 mm by 2100 and +116.32 ± 66.87 mm by 2300, with ice-shelf collapse on. This would involve significant loss of land ice, ungrounding of ice in the Bellingshausen Sea, and significant thinning in the George VI sector and Palmer Land.

Marine ecosystems

Marine ecosystems are already being impacted by warming. The increased release of sediments at retreating glacier fronts affects organisms that live on the sea bed. Sea ice lows have meant that the stable landfast sea ice that Emperor penguins rely on for breeding has been lost, leading to the loss of breeding colonies. A continued reductions in sea ice would further impact emperor penguins.

Under a warmer climate, krill are likely to continue their southward contraction, which would negatively impact the predators that feed upon them. Because krill feed on the algae that live in sea ice, they are dependent upon it, and severe sea ice reductions would limit their habitats. Whales, seals and penguins all depend on krill. Antarctic krill are also an important fishery, and perform an important ecosystem service through carbon sequestration, exporting carbon to the sea floor.

Increased surface melt and rain will impact ice-dependent species such as Adelie penguins and chinstrap penguins. Their chicks have fluffy down that is not waterproof, and they cannot tolerate either their eggs or chicks getting wet. Gentoo penguins are replacing Adelie penguins on the western Antarctic Peninsula since they are less dependent on krill, and more tolerant of rainy conditions.

Finally, invasive species are more likely with increased storminess, reduced sea ice and warmer oceans.

Terrestrial ecosystems

Terrestrial fauna on the Antarctic Peninsula largely consists of invertebrates, with high levels of endemic species. They are threatened by changes in temperature, precipitation volume and phase change (solid snow versus rain water). Vegetation may expand as a result of more liquid water availability, but increased liquid precipitation risks flooding terrestrial ecosystems. Increased liquid water can also acceleate snow loss, decreasing the snow algae habitat (an important primary producer).

Snow algae is an important carbon sink, an important influence on albedo, and influences nutrient provision to downstream terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Risk to operations

The UK’s Antarctic Strategy is commited to upholding the Antarctic Treaty and maintaining ‘peaceful and lawful usage’ of the Antarctic Peninsula. Environmental changes on the Peninsula are creating a riskier and more challenging operational environment, alongside increased shipping, tourism and fishing. A warmer world may place stress on the Antarctic Treaty System and associated legal instruments.

The majority of Antarctic tourism and krill fishing occurs on the Peninsula, with research activity focused at the 44 research bases. Increased precipitation falling as rain will challenge Antarctic field equipment and infrastructure, which is not designed to cope with this. Refreezing rain is debilitating for airstrips and disrupts operations. Marine operations will be challenged by changes in landfast sea ice and increased numbers of icebergs.

Coastal erosion, sea level change, permafrost melt, extreme weather events, rainfall, sea ice change and glacier recession may mean that research infrastructure has to be relocated, and may challenge infrastructure resilience.

Increased geopolitical interest means that Antarctic infrastructure is likely to expand further, because research bases are a way for nations to demonstrate ‘effective presence’. Tourism is increasing rapidly, and the productive waters are attracting increasing commerical fishing.

Whatever scenario we follow, it is likely that the Antarctic Treaty and its associated instruments will be placed under further stress. Competition for krill fisheries may challenge further progress on marine protected areas. The Antarctic Peninsula will likely become a riskier operational environment, with risks of pollution incidents, accidents and disasters involving tourists, fishing operations and national scientific operators.

Which way forward for the Antarctic Peninsula?

The way forward is clear. Meeting the Net Zero targets and pledges submitted to COP30 would limit global warming to less than 2°C. If global warming exceeds this threshold, we are committed to irreversible and catastrophic change on the Peninsula. Not only will we threaten iconic and special wildlife, but we will also be directly impacted, through amplification of polar warming, reduced ability of the Southern Ocean to take up heat and carbon dioxide, changed oceanic circulation and sea level rise. The Antarctic Peninsula is changing rapidly, and is the first alarm bell for the Antarctic continent, as these changes will be felt increasingly across coastal Antarctica.

The choices we make today will set the future for the Antarctic Peninsula. We cannot afford to delay. We need to urgently implement the Net Zero pledges and pledges that will protect this unique and special environment.

Further coverage

Grantham Institute Policy Brief

The Conversation (to come)